OnPoint Subscriber Exclusive

Longer Reads provide in-depth analysis of the ideas and forces shaping politics, economics, international affairs, and more.

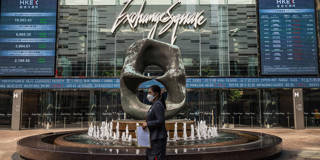

How to Kill Chinese Dynamism

Those who believe that Chinese entrepreneurship and growth have thrived under a magical formula of statism ignore the role that Hong Kong played in providing the conventional pillars of market finance and the rule of law. Without this escape valve, China's great economic success story never would have happened.

BOSTON – In Lonely Ideas: Can Russia Compete?, MIT historian of science Loren Graham shows that many technologies pioneered by Soviet and post-Soviet Russia – including various weapons, improved railroads, and lasers – nonetheless failed to benefit the national economy in any substantial way. The reason for this abysmal failure, he concludes, is Russia’s lack of entrepreneurship.