A review of the policy debates of the post-crisis years suggests that flawed macroeconomic theories were given too much weight for too long. The result has been slower growth, lost economic capacity, and surplus misery for millions of people around the world.

LONDON – Ten years after the 2007-2008 financial crisis, it is worth asking where the world’s developed economies are today, where they would have been had there been no crisis, and, perhaps more important, where they might have been had different policy choices prevailed before and after the collapse.

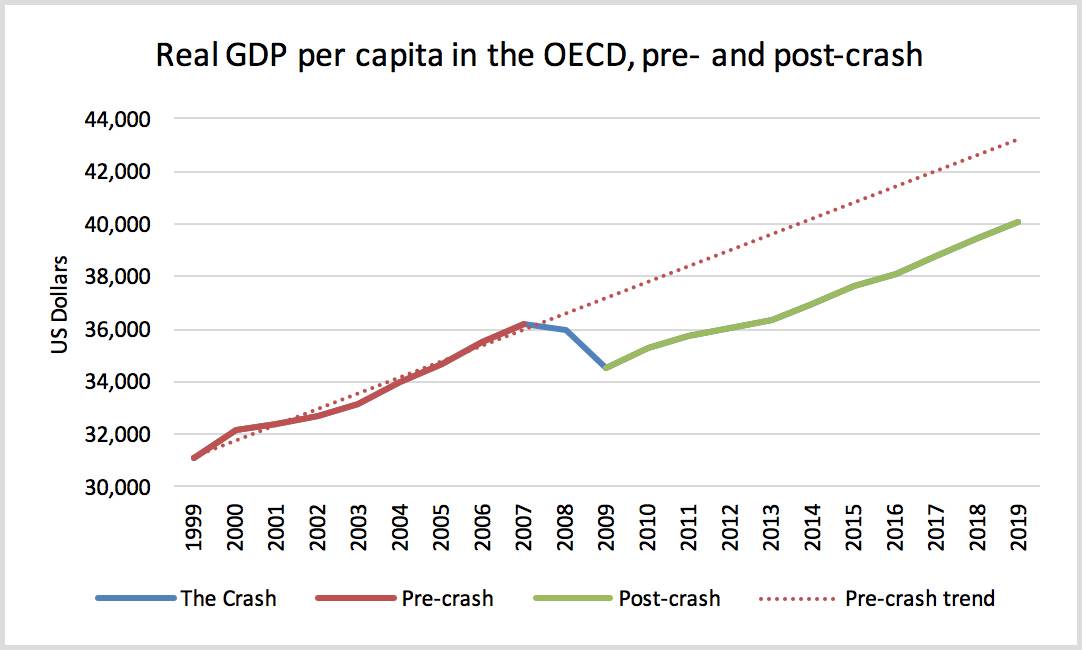

The first two questions can be answered with a single graph, which shows real (inflation-adjusted) per capita GDP growth for OECD countries from 2000 to 2018. As a bloc, the OECD spent five years getting back to where it was just before the crash (the eurozone took two years longer). And its average annual growth rate (1.5%) has remained at three-quarters of the pre-crash level (2%).

Figure 1

The red dotted line shows where the OECD would be but for the crisis, and the green line shows where it will be if growth continues at its lower post-crash rate. By 2019, each person in the bloc will have suffered a cumulative loss of $32,000, on average.

The question of where we would be had different policies been adopted is, no surprise, much harder to answer. Could the crisis have been avoided in the first place? In retrospect, there is a strong case to be made that it could have been. We now know that financial-market liberalization, influenced by “efficient market theory,” made banks inherently more vulnerable to contagion. But what about the effects of post-crash policies? The insight and analysis offered in recent years by Project Syndicate commentators, many of whom have led the economic-policy debate since the crisis, help to answer that question.

Missed Opportunities

For his part, Nobel laureate economist Joseph E. Stiglitz frames the overall debate by emphasizing the role that policy can play in determining not just the depth of a crisis, but also its duration. “Success should not be measured by the fact that recovery eventually occurs,” he writes, “but in how quickly it takes hold and how extensive the damage caused by the slump.”

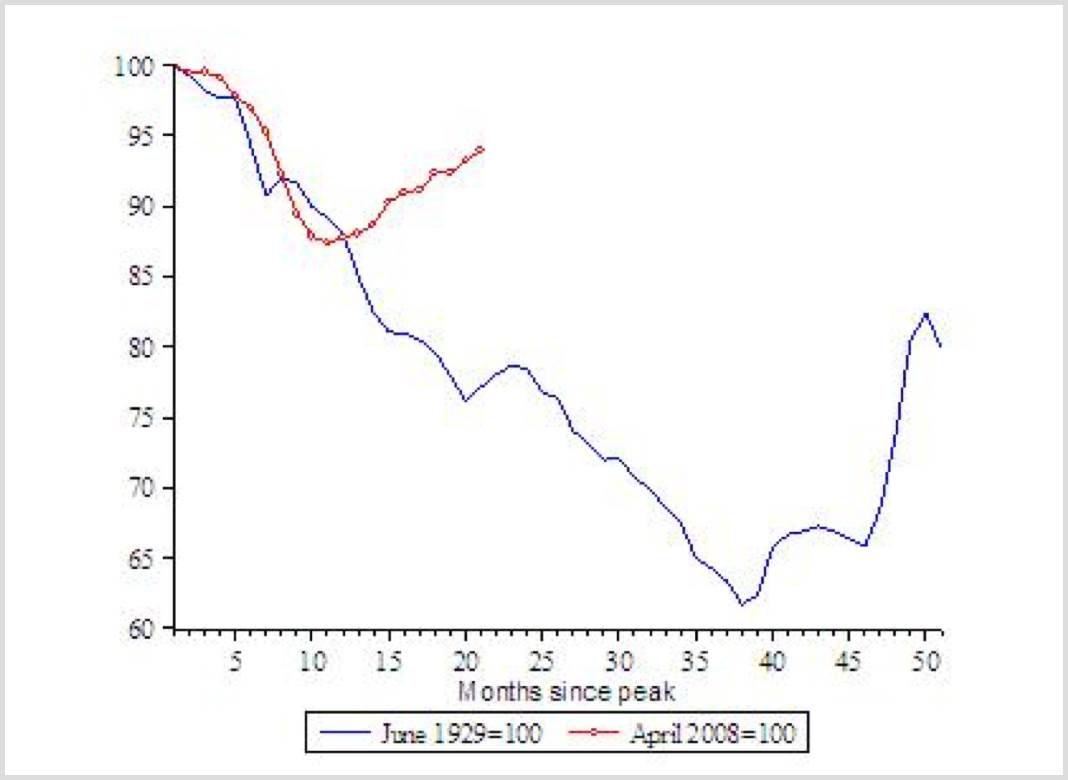

Looking back, it is clear that policy interventions immediately following the 2008 crash did make a difference, at least in the near term. As the graph below shows, the 2008 collapse was as steep as that of 1929, but it lasted for a much shorter time. Unlike US Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon in 1929, no one in 2008 really wanted to “Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate,” in order to “purge the rottenness out of the system.” In other words, no one wanted to create the conditions for another Adolf Hitler to emerge.

Instead, the 2008 crisis was met not by belt-tightening, but by globally coordinated monetary and fiscal expansions, particularly on the part of China. As J. Bradford DeLong of the University of California, Berkeley, notes, “The aftermath of the 2007-2008 financial crash was painful, to be sure; but it did not become a repeat of the Great Depression, in terms of falling output and employment.” Within four quarters, “green shoots” of recovery were appearing; that didn’t happen for 13 quarters after the 1929 crash.

Yet in 2010, before the shoots had time to flower, OECD governments rolled back their stimulus policies and introduced austerity policies, or “fiscal consolidation,” designed to eliminate deficits and put debt/GDP ratios on a “declining path.” It is now generally agreed that these measures slowed down the recovery, and probably reduced the advanced economies’ productive capacity as well. In Europe, Stiglitz observed in 2014, the period of austerity had “been an utter and unmitigated disaster.” And in the United States, notes DeLong, “relative performance after the Great Recession [has been] nothing short of appalling.”

Though the depressive effects of austerity were partly offset by expansionary monetary policies such as quantitative easing (QE), the mismatch itself has left a legacy of financial fragility. While per capita GDP has recovered in most OECD countries, median income has lagged behind, implying that there was a great deal of collateral damage that has still not been repaired.

Of Confidence and Complacency

After the immediate threat of a depression was averted, economists vigorously debated the merits of withdrawing stimulus so early in the recovery. Their arguments, which can be broken down into four identifiable positions, open a window onto the role that macroeconomic theory played in the crisis.

Those in the first camp claimed that fiscal austerity – that is, deficit reduction – would accelerate the recovery in the short run. Those in the second camp countered that austerity would have short-run costs, but argued that it would be worth the long-run benefits. A third camp, comprising Keynesians, argued unambiguously against austerity. And the fourth camp maintained that, regardless of whether austerity was right, it was unavoidable, given the situation many countries had created for themselves.

The first, least cautious argument for fiscal austerity came from Harvard University economist Alberto Alesina, who was much in vogue during the early phase of the crisis. In April 2010, Alesina published a paper assuring European finance ministers that, “Many even sharp reductions of budget deficits have been accompanied and immediately followed by sustained growth rather than recessions even in the very short run.” Alesina based this conclusion on historical studies of fiscal contractions, and argued that a credible program of deficit reduction would boost confidence enough to offset any adverse effects of the fiscal contraction itself.

A number of Project Syndicate commentators took Alesina to task for these claims. Nobel laureate economist Robert J. Shiller countered that, contrary to Alesina’s assurances, “There is no abstract theory that can predict how people will react to an austerity program.” Writing in 2012, Shiller correctly predicted that “austerity programs in Europe and elsewhere appear likely to yield disappointing results.”

Similarly, Harvard’s Jeffrey Frankel pointed out in May 2013 that Alesina’s co-author on two influential papers, Robert Perotti, had recanted, having identified flaws in their methodology. Following more criticism of his methodology by the International Monetary Fund and the OECD, Alesina himself became considerably more circumspect about the promise of austerity. Of course, by then, he had already contributed his mite to the sum of human misery.

Dubious Debts

Out of the Alesina wreckage emerged another case for austerity, based on the doctrine of “short-run pain for long-run gain.” As Daniel Gros of the Center for European Policy Studies explained in August 2013, “Austerity always involves huge social costs,” yet “almost all economic models imply that a cut in expenditures today should lead to higher GDP in the long run, because it allows for lower taxes (and thus reduces economic distortions).”

The most influential version of the “short-run pain for long-run gain” argument came from Harvard’s Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen M. Reinhart. In their 2009 book, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Rogoff and Reinhart attributed the “vast range of [financial] crises” throughout modern history to “excessive debt accumulation.” And in a June 2012 Project Syndicatecommentary, Rogoff claimed that public debt levels above 90% of GDP imposed “stunning” cumulative costs on growth. The implication was clear: only by immediately reducing the growth of public debt could advanced economies avoid prolonged malaise.

This, it turned out, was another dubious recipe for recovery. Because Rogoff and Reinhart found a historical correlation between high debt and slow growth, they presumed that high debt caused slow growth. Yet it is just as likely that slow growth had caused high debt. Rogoff’s theory had led him to a particular interpretation of the data. Or, as Oscar Wilde wrote of Wordsworth, “He found in stones the sermons he had already hidden there.”

The sermons preached by Alesina, Rogoff, and Reinhart held that the state was inherently less efficient and more corrupt than the private sector. Thus, they believed that the growth of state spending was bound to impede the growth of income and wealth. It is little wonder that former British Chancellor George Osborne, who strongly supported reducing the size of the state, credited Reinhart and Rogoff for influencing his thinking.

Use It or Lose It

While the Rogoff/Reinhart school was calling for rapid reductions in the debt-to-GDP ratio to boost growth, Keynesians pointed out that austerity itself was limiting growth, by reducing demand. The Keynesian argument was straightforward. Because the slump had been caused by an increase in private-sector saving, the recovery would have to be driven by government dissaving – deficit spending – to offset the negative impact on aggregate demand.

As Mark Blyth of Brown University noted in 2013, the attempt by European governments at the time to increase their savings was having a ruinous effect. “GDP has collapsed,” he observed, and “unemployment in the eurozone has skyrocketed to an average rate of roughly 12%, with more than 50% youth unemployment in the periphery countries.”

At a time when democracy is under threat, there is an urgent need for incisive, informed analysis of the issues and questions driving the news – just what PS has always provided. Subscribe now and save $50 on a new subscription.

Subscribe Now

In July 2012, DeLong acknowledged that the alternative to austerity – fiscal expansion – would indeed raise the current debt/GDP ratio in the short term. But, by stimulating investment, it would produce faster economic growth and thus reduce the debt ratio in the medium term – the exact reverse of Rogoff’s formulation. At issue was the effect of changes in the numerator (debt) on the denominator (national income). The question, then, was whether austerity would, under the circumstances of the day, fetter or spur the growth of national income.

DeLong’s main argument was that fiscal consolidation turns cyclical unemployment into structural unemployment, and thus reduces the economy’s future productive capacity. When workers experience long-term unemployment, DeLong explains, they can fall into a vicious cycle in which they become even less employable with the passage of time. The problem, notes Nouriel Roubini of New York University, is that “if workers remain unemployed for too long, they lose their skills and human capital.” And this erosion of the skills base can lead to “hysteresis,” such that “a persistent cyclical downturn or weak recovery (like the one we have experienced since 2008) can reduce potential growth.”

Hysteresis, which helps to explain the decline in the growth rate shown in Figure 1, can also result from a large-scale switch to inferior employment. Flexible labor markets in the US and the United Kingdom have enabled both economies to return to pre-crisis unemployment levels (in the range of 4-5%). But the official unemployment rate excludes millions of workers who are involuntarily employed part-time, as well as others doing what the anthropologist David Graeber has described as “bullshit jobs.”

In short, fiscal consolidation after a crisis doesn’t necessarily produce a persistently elevated level of unemployment, as classical Keynesian theory supposed. But it does slow down productivity and growth, whether through high long-term unemployment, as in countries such as Greece, Spain, and Italy, or through high underemployment, as in the US and the UK.

I find the Keynesian perspective more intuitively appealing than the Rogoffian one. It stands to reason that long spells of unemployment or inferior employment will undermine a country’s output potential. But to argue that an “abnormal” level of national debt does the same, one must also demonstrate that state spending – whether tax- or bond-financed – hurts long-term growth by reducing the economy’s efficiency. And such a claim relies heavily on ideology.

When to Intervene?

Of course, past policy follies or current constraints can leave a country with no alternative to austerity. In 2010, the Princeton University historian Harold James pointed out that a country’s creditors can sometimes force it to undergo “fiscal consolidation.” This is particularly true for countries with a fixed exchange rate, such as those that adhered to the gold standard during the Great Depression. James’s emphasis on external policy constraints helps to explain the stagnation of the eurozone, where the demands of a mini-gold standard – the single currency – limited member states’ monetary- and fiscal-policy options during the downturn.

In the early years of the crisis, Greece stood out as an awful warning to others. Ricardo Hausmann of Harvard University notes that, “by 2007, Greece was spending more than 14% of GDP in excess of what it was producing,” with the gap being “mostly fiscal and used for consumption, not investment.” Still, Laura Tyson of the University of California, Berkeley, contends that Europe’s bondholders, led by Germany, conflated Greek public profligacy with private greed and myopia. Expanding on this point, Simon Johnson of MIT observed that while debtor countries suffered dearly for over-borrowing, banks faced almost no penalties for over-lending.

Many discussions about the feasibility of different fiscal policies revolve around the mysterious idea of “fiscal space.” In Keynesian theory, fiscal space is a measure of slack or spare capacity in the economy. If the multiplier is positive, then there is some room for fiscal expansion.

By contrast, the hardest version of anti-Keynesian theory – Ricardian equivalence – holds the economy to be always fully employed. Resources commandeered by government will thus deprive the private sector of their use, implying that fiscal space is zero. Between these two views, some posit that fiscal space is elastic, determined by psychology, politics, and institutions, and encapsulated in the umbrella term “state of confidence.”

For example, in September 2016, Roubini wrote that, “thanks to painful austerity, deficits and debts have fallen, meaning that most advanced economies now have some fiscal space to boost demand.” Note that this argument implies a psychological or institutional definition of fiscal space. In this case, fiscal space is not based on the existence of spare capacity. Rather, it means that bondholders are willing to buy government debt at low interest rates, or that the deficit has fallen below some institutionally prescribed level.

Keynesians tend to be suspicious of this type of argument, because it leaves the definition of fiscal space to the bond markets, and is not based on an objective measure of economic slack. Moreover, implying that fiscal space can be created through prior “austerity” is like saying that an auto repair shop should damage a customer’s car to win his consent to make repairs.

The False Promise of Monetary Miracles

In the US, the UK, and the eurozone (after March 2015), economic policymakers sought to offset fiscal contraction with monetary expansion, chiefly by purchasing massive quantities of government bonds. The consensus view is that QE was modestly successful, but fell far short of fulfilling monetary policymakers’ goals. Central bankers had assumed, incorrectly, that if they simply printed money, it would automatically enter the spending stream.

This faulty theory of money was driven by pure ideology, as the Nobel laureate economist Robert E. Lucas, Jr. unwittingly intimated in a December 2008 Wall Street Journalcommentary. Unlike fiscal expansion, Lucas observed, monetary expansion “entails no new government enterprises, no government equity in private enterprises, no price fixing or other controls on the operation of individual business, and no government role in the allocation of capital across different activities.” In his view, these are all “important virtues” – which is to say, a faulty theory is better than one that entails any increased role for the state.

All told, I believe the policies since the financial crisis have extended the damage of the slump itself. Looking ahead, we will have to confront not just the problem of waste or missed opportunities, but of regression. We are restarting economic life with dimmer long-term prospects than we otherwise would have had.

To have unlimited access to our content including in-depth commentaries, book reviews, exclusive interviews, PS OnPoint and PS The Big Picture, please subscribe

Although Americans – and the world – have been spared the kind of agonizing uncertainty that followed the 2020 election, a different kind of uncertainty has set in. While few doubt that Donald Trump's comeback will have far-reaching implications, most observers are only beginning to come to grips with what those could be.

consider what the outcome of the 2024 US presidential election will mean for America and the world.

Anders Åslund

considers what the US presidential election will mean for Ukraine, says that only a humiliating loss in the war could threaten Vladimir Putin’s position, urges the EU to take additional steps to ensure a rapid and successful Ukrainian accession, and more.

From the economy to foreign policy to democratic institutions, the two US presidential candidates, Kamala Harris and Donald Trump, promise to pursue radically different agendas, reflecting sharply diverging visions for the United States and the world. Why is the race so nail-bitingly close, and how might the outcome change America?

Log in/Register

Please log in or register to continue. Registration is free.

LONDON – Ten years after the 2007-2008 financial crisis, it is worth asking where the world’s developed economies are today, where they would have been had there been no crisis, and, perhaps more important, where they might have been had different policy choices prevailed before and after the collapse.

The first two questions can be answered with a single graph, which shows real (inflation-adjusted) per capita GDP growth for OECD countries from 2000 to 2018. As a bloc, the OECD spent five years getting back to where it was just before the crash (the eurozone took two years longer). And its average annual growth rate (1.5%) has remained at three-quarters of the pre-crash level (2%).

Figure 1

The red dotted line shows where the OECD would be but for the crisis, and the green line shows where it will be if growth continues at its lower post-crash rate. By 2019, each person in the bloc will have suffered a cumulative loss of $32,000, on average.

The question of where we would be had different policies been adopted is, no surprise, much harder to answer. Could the crisis have been avoided in the first place? In retrospect, there is a strong case to be made that it could have been. We now know that financial-market liberalization, influenced by “efficient market theory,” made banks inherently more vulnerable to contagion. But what about the effects of post-crash policies? The insight and analysis offered in recent years by Project Syndicate commentators, many of whom have led the economic-policy debate since the crisis, help to answer that question.

Missed Opportunities

For his part, Nobel laureate economist Joseph E. Stiglitz frames the overall debate by emphasizing the role that policy can play in determining not just the depth of a crisis, but also its duration. “Success should not be measured by the fact that recovery eventually occurs,” he writes, “but in how quickly it takes hold and how extensive the damage caused by the slump.”

Looking back, it is clear that policy interventions immediately following the 2008 crash did make a difference, at least in the near term. As the graph below shows, the 2008 collapse was as steep as that of 1929, but it lasted for a much shorter time. Unlike US Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon in 1929, no one in 2008 really wanted to “Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate,” in order to “purge the rottenness out of the system.” In other words, no one wanted to create the conditions for another Adolf Hitler to emerge.

Figure 2

Note: A comparison of global industrial production after the crashes of 1929 and 2008.

Instead, the 2008 crisis was met not by belt-tightening, but by globally coordinated monetary and fiscal expansions, particularly on the part of China. As J. Bradford DeLong of the University of California, Berkeley, notes, “The aftermath of the 2007-2008 financial crash was painful, to be sure; but it did not become a repeat of the Great Depression, in terms of falling output and employment.” Within four quarters, “green shoots” of recovery were appearing; that didn’t happen for 13 quarters after the 1929 crash.

Yet in 2010, before the shoots had time to flower, OECD governments rolled back their stimulus policies and introduced austerity policies, or “fiscal consolidation,” designed to eliminate deficits and put debt/GDP ratios on a “declining path.” It is now generally agreed that these measures slowed down the recovery, and probably reduced the advanced economies’ productive capacity as well. In Europe, Stiglitz observed in 2014, the period of austerity had “been an utter and unmitigated disaster.” And in the United States, notes DeLong, “relative performance after the Great Recession [has been] nothing short of appalling.”

Though the depressive effects of austerity were partly offset by expansionary monetary policies such as quantitative easing (QE), the mismatch itself has left a legacy of financial fragility. While per capita GDP has recovered in most OECD countries, median income has lagged behind, implying that there was a great deal of collateral damage that has still not been repaired.

Of Confidence and Complacency

After the immediate threat of a depression was averted, economists vigorously debated the merits of withdrawing stimulus so early in the recovery. Their arguments, which can be broken down into four identifiable positions, open a window onto the role that macroeconomic theory played in the crisis.

Those in the first camp claimed that fiscal austerity – that is, deficit reduction – would accelerate the recovery in the short run. Those in the second camp countered that austerity would have short-run costs, but argued that it would be worth the long-run benefits. A third camp, comprising Keynesians, argued unambiguously against austerity. And the fourth camp maintained that, regardless of whether austerity was right, it was unavoidable, given the situation many countries had created for themselves.

The first, least cautious argument for fiscal austerity came from Harvard University economist Alberto Alesina, who was much in vogue during the early phase of the crisis. In April 2010, Alesina published a paper assuring European finance ministers that, “Many even sharp reductions of budget deficits have been accompanied and immediately followed by sustained growth rather than recessions even in the very short run.” Alesina based this conclusion on historical studies of fiscal contractions, and argued that a credible program of deficit reduction would boost confidence enough to offset any adverse effects of the fiscal contraction itself.

A number of Project Syndicate commentators took Alesina to task for these claims. Nobel laureate economist Robert J. Shiller countered that, contrary to Alesina’s assurances, “There is no abstract theory that can predict how people will react to an austerity program.” Writing in 2012, Shiller correctly predicted that “austerity programs in Europe and elsewhere appear likely to yield disappointing results.”

Similarly, Harvard’s Jeffrey Frankel pointed out in May 2013 that Alesina’s co-author on two influential papers, Robert Perotti, had recanted, having identified flaws in their methodology. Following more criticism of his methodology by the International Monetary Fund and the OECD, Alesina himself became considerably more circumspect about the promise of austerity. Of course, by then, he had already contributed his mite to the sum of human misery.

Dubious Debts

Out of the Alesina wreckage emerged another case for austerity, based on the doctrine of “short-run pain for long-run gain.” As Daniel Gros of the Center for European Policy Studies explained in August 2013, “Austerity always involves huge social costs,” yet “almost all economic models imply that a cut in expenditures today should lead to higher GDP in the long run, because it allows for lower taxes (and thus reduces economic distortions).”

The most influential version of the “short-run pain for long-run gain” argument came from Harvard’s Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen M. Reinhart. In their 2009 book, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Rogoff and Reinhart attributed the “vast range of [financial] crises” throughout modern history to “excessive debt accumulation.” And in a June 2012 Project Syndicatecommentary, Rogoff claimed that public debt levels above 90% of GDP imposed “stunning” cumulative costs on growth. The implication was clear: only by immediately reducing the growth of public debt could advanced economies avoid prolonged malaise.

This, it turned out, was another dubious recipe for recovery. Because Rogoff and Reinhart found a historical correlation between high debt and slow growth, they presumed that high debt caused slow growth. Yet it is just as likely that slow growth had caused high debt. Rogoff’s theory had led him to a particular interpretation of the data. Or, as Oscar Wilde wrote of Wordsworth, “He found in stones the sermons he had already hidden there.”

The sermons preached by Alesina, Rogoff, and Reinhart held that the state was inherently less efficient and more corrupt than the private sector. Thus, they believed that the growth of state spending was bound to impede the growth of income and wealth. It is little wonder that former British Chancellor George Osborne, who strongly supported reducing the size of the state, credited Reinhart and Rogoff for influencing his thinking.

Use It or Lose It

While the Rogoff/Reinhart school was calling for rapid reductions in the debt-to-GDP ratio to boost growth, Keynesians pointed out that austerity itself was limiting growth, by reducing demand. The Keynesian argument was straightforward. Because the slump had been caused by an increase in private-sector saving, the recovery would have to be driven by government dissaving – deficit spending – to offset the negative impact on aggregate demand.

As Mark Blyth of Brown University noted in 2013, the attempt by European governments at the time to increase their savings was having a ruinous effect. “GDP has collapsed,” he observed, and “unemployment in the eurozone has skyrocketed to an average rate of roughly 12%, with more than 50% youth unemployment in the periphery countries.”

HOLIDAY SALE: PS for less than $0.7 per week

At a time when democracy is under threat, there is an urgent need for incisive, informed analysis of the issues and questions driving the news – just what PS has always provided. Subscribe now and save $50 on a new subscription.

Subscribe Now

In July 2012, DeLong acknowledged that the alternative to austerity – fiscal expansion – would indeed raise the current debt/GDP ratio in the short term. But, by stimulating investment, it would produce faster economic growth and thus reduce the debt ratio in the medium term – the exact reverse of Rogoff’s formulation. At issue was the effect of changes in the numerator (debt) on the denominator (national income). The question, then, was whether austerity would, under the circumstances of the day, fetter or spur the growth of national income.

DeLong’s main argument was that fiscal consolidation turns cyclical unemployment into structural unemployment, and thus reduces the economy’s future productive capacity. When workers experience long-term unemployment, DeLong explains, they can fall into a vicious cycle in which they become even less employable with the passage of time. The problem, notes Nouriel Roubini of New York University, is that “if workers remain unemployed for too long, they lose their skills and human capital.” And this erosion of the skills base can lead to “hysteresis,” such that “a persistent cyclical downturn or weak recovery (like the one we have experienced since 2008) can reduce potential growth.”

Hysteresis, which helps to explain the decline in the growth rate shown in Figure 1, can also result from a large-scale switch to inferior employment. Flexible labor markets in the US and the United Kingdom have enabled both economies to return to pre-crisis unemployment levels (in the range of 4-5%). But the official unemployment rate excludes millions of workers who are involuntarily employed part-time, as well as others doing what the anthropologist David Graeber has described as “bullshit jobs.”

In short, fiscal consolidation after a crisis doesn’t necessarily produce a persistently elevated level of unemployment, as classical Keynesian theory supposed. But it does slow down productivity and growth, whether through high long-term unemployment, as in countries such as Greece, Spain, and Italy, or through high underemployment, as in the US and the UK.

I find the Keynesian perspective more intuitively appealing than the Rogoffian one. It stands to reason that long spells of unemployment or inferior employment will undermine a country’s output potential. But to argue that an “abnormal” level of national debt does the same, one must also demonstrate that state spending – whether tax- or bond-financed – hurts long-term growth by reducing the economy’s efficiency. And such a claim relies heavily on ideology.

When to Intervene?

Of course, past policy follies or current constraints can leave a country with no alternative to austerity. In 2010, the Princeton University historian Harold James pointed out that a country’s creditors can sometimes force it to undergo “fiscal consolidation.” This is particularly true for countries with a fixed exchange rate, such as those that adhered to the gold standard during the Great Depression. James’s emphasis on external policy constraints helps to explain the stagnation of the eurozone, where the demands of a mini-gold standard – the single currency – limited member states’ monetary- and fiscal-policy options during the downturn.

In the early years of the crisis, Greece stood out as an awful warning to others. Ricardo Hausmann of Harvard University notes that, “by 2007, Greece was spending more than 14% of GDP in excess of what it was producing,” with the gap being “mostly fiscal and used for consumption, not investment.” Still, Laura Tyson of the University of California, Berkeley, contends that Europe’s bondholders, led by Germany, conflated Greek public profligacy with private greed and myopia. Expanding on this point, Simon Johnson of MIT observed that while debtor countries suffered dearly for over-borrowing, banks faced almost no penalties for over-lending.

Many discussions about the feasibility of different fiscal policies revolve around the mysterious idea of “fiscal space.” In Keynesian theory, fiscal space is a measure of slack or spare capacity in the economy. If the multiplier is positive, then there is some room for fiscal expansion.

By contrast, the hardest version of anti-Keynesian theory – Ricardian equivalence – holds the economy to be always fully employed. Resources commandeered by government will thus deprive the private sector of their use, implying that fiscal space is zero. Between these two views, some posit that fiscal space is elastic, determined by psychology, politics, and institutions, and encapsulated in the umbrella term “state of confidence.”

For example, in September 2016, Roubini wrote that, “thanks to painful austerity, deficits and debts have fallen, meaning that most advanced economies now have some fiscal space to boost demand.” Note that this argument implies a psychological or institutional definition of fiscal space. In this case, fiscal space is not based on the existence of spare capacity. Rather, it means that bondholders are willing to buy government debt at low interest rates, or that the deficit has fallen below some institutionally prescribed level.

Keynesians tend to be suspicious of this type of argument, because it leaves the definition of fiscal space to the bond markets, and is not based on an objective measure of economic slack. Moreover, implying that fiscal space can be created through prior “austerity” is like saying that an auto repair shop should damage a customer’s car to win his consent to make repairs.

The False Promise of Monetary Miracles

In the US, the UK, and the eurozone (after March 2015), economic policymakers sought to offset fiscal contraction with monetary expansion, chiefly by purchasing massive quantities of government bonds. The consensus view is that QE was modestly successful, but fell far short of fulfilling monetary policymakers’ goals. Central bankers had assumed, incorrectly, that if they simply printed money, it would automatically enter the spending stream.

This faulty theory of money was driven by pure ideology, as the Nobel laureate economist Robert E. Lucas, Jr. unwittingly intimated in a December 2008 Wall Street Journalcommentary. Unlike fiscal expansion, Lucas observed, monetary expansion “entails no new government enterprises, no government equity in private enterprises, no price fixing or other controls on the operation of individual business, and no government role in the allocation of capital across different activities.” In his view, these are all “important virtues” – which is to say, a faulty theory is better than one that entails any increased role for the state.

All told, I believe the policies since the financial crisis have extended the damage of the slump itself. Looking ahead, we will have to confront not just the problem of waste or missed opportunities, but of regression. We are restarting economic life with dimmer long-term prospects than we otherwise would have had.